Table of Contents

- Introduction & History

- Basics

- Data Types & Variables

- Input/Output Operations

- Control Flow

- Functions

- Data Structures

- Pointers

- Structs & Methods

- Interfaces

- Generics

- Concurrency

- Error Handling

- Testing

- Standard Library & Packages

- Advanced Concepts

Introduction & History

What is Go?

Go (often referred to as Golang to avoid ambiguity and because of its former domain name golang.org) is:

- A statically typed (declare variable type or inferred), compiled, high-level general-purpose programming language

- Often called "C for the 21st century"

- Popular choice for high-performance server-side applications

- The language that built tools like Docker, Kubernetes, CockroachDB, and Dgraph

Six Main Points About Go:

- Statically typed - Variables must be declared or type inferred

- Strongly typed - Cannot mix types (e.g., can't add number and string)

- Compiled - Source code compiled to machine code for performance

- Fast compile time - Innovations in dependency analysis enable extremely fast compilation

- Built-in concurrency - Goroutines allow functions to run simultaneously on multiple CPU threads

- Simplicity - Features like garbage collection make programming easier

Design Philosophy

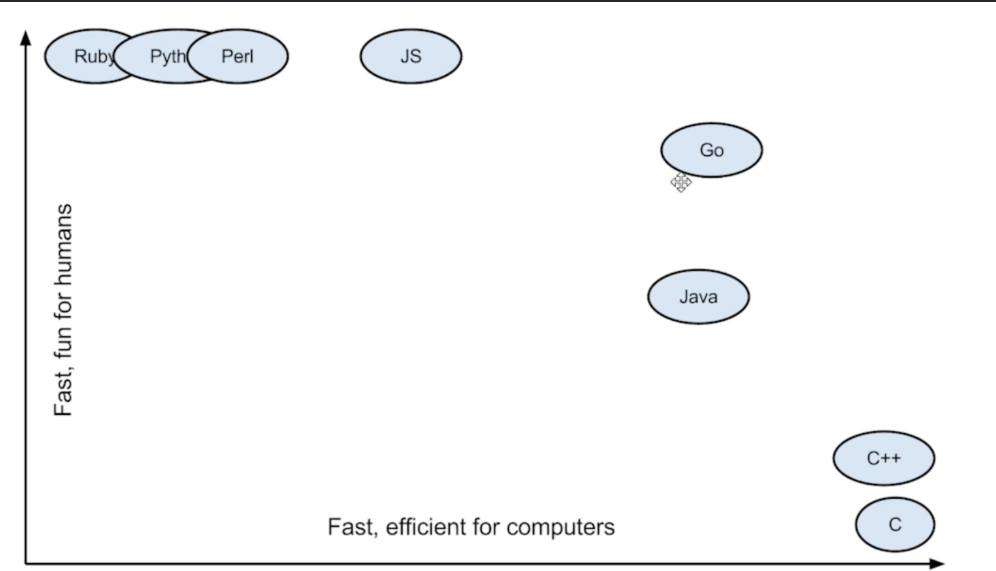

Go was designed at Google in 2007 to improve programming productivity in an era of multicore, networked machines and large codebases. The designers wanted to address criticisms of other languages in use at Google while keeping their useful characteristics:

- Static typing and run-time efficiency (like C)

- Readability and usability (like Python)

- High-performance networking and multiprocessing

The designers were primarily motivated by their shared dislike of C++.

Key Features:

- Source code compiles down to machine code, which generally outperforms interpreted languages

- Fast compile times made possible by innovations in dependency analysis

- Package and module system makes it easy to import/export code between projects

- Pointers without pointer arithmetic - Store memory addresses safely without the dangerous and unpredictable behavior of pointer arithmetic

- Concurrency with goroutines - Functions can run simultaneously utilizing multiple CPU threads

About the Creators

Created at Google by:

- Robert Griesemer (Hotspot, JVM)

- Rob Pike (Unix, UTF-8)

- Ken Thompson (B, C, Unix, UTF-8)

Timeline

- 2005: First dual-core processors emerge

- 2006: Go development started

- 2007: Go designed at Google

- 2009: Open sourced on November 10, 2009

Fun Fact: In the Go playground, time begins at 2009-11-10 23:00:00 UTC - Go's birthday! The announcement was titled "Hey! Ho! Let's Go!" (a Ramones song reference).

Basics

Key Concepts

- Every Go program is made up of packages

- Programs start running in package main

- Files using a package start with

package <name>(e.g.,import "math/rand"→ files start withpackage rand) - Capitalized names are exported and can be used outside the package

- Constants cannot be declared using

:=syntax

Package Structure

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, World!")

}Environment

go env # View all environment variables

go env GOARCH GOOS # View architecture and OSBuild vs Install

go build: Compiles executable and moves it to destinationgo install: Does more - moves executable to$GOPATH/binand caches non-main packages to$GOPATH/pkgfor faster future compilation

Go Runtime

The Go runtime system manages:

- Goroutine management: Creates, destroys, and schedules goroutines

- Garbage collection: Automatically frees unused memory

- Memory management: Allocates and deallocates memory

- Channel management: Manages communication between goroutines

- Stack management: Each goroutine has its own stack

Data Types & Variables

Data Types

// Boolean

bool

// String

string

// Integers (unsigned)

// Note: ranges assume typical implementation on common architectures

uint // platform-dependent (32 or 64 bit)

uint8 (0 to 255)

uint16 (0 to 65535)

uint32 (0 to 4294967295)

uint64 (0 to 18446744073709551615)

uintptr // platform-dependent (pointer-sized unsigned int)

// Integers (signed)

int // platform-dependent (32 or 64 bit)

int8 (-128 to 127)

int16 (-32768 to 32767)

int32 (-2147483648 to 2147483647)

int64 (-9223372036854775808 to 9223372036854775807)

// Floating point

float32 float64

// Aliases

byte // alias for uint8

rune // alias for int32 (represents a Unicode code point)

// Complex numbers

complex64 complex128Variable Declaration

// Method 1: Declare then assign

var name string

name = "John"

// Method 2: Declare and initialize

var name string = "John"

// Method 3: Multiple variables

var b, c int = 1, 2

// Method 4: Type inference

var name = "John"

// Method 5: Short declaration (inside functions only)

name := "John"

// Outside a function, every statement begins with a keyword (var, func, etc.)

// so the := construct is not availableType Inference

%T // Format specifier to get type of variableConstants

const pi = 3.14

// Constants cannot be declared using := syntax

// var name := "test" // This works for variables

// const name := "test" // ERROR! Must use: const name = "test"

// Numeric constants are high-precision values

const d = 3e20 // 300,000,000,000,000,000,000Constant expressions perform arithmetic with arbitrary precision:

The value 3e20 equals 300,000,000,000,000,000,000. This number is HUGE - it's too big to fit in a standard int64 (which maxes out at around 9 quintillion).

However, Go allows you to define this as a constant because constants are untyped and have arbitrary precision until they're used in a context that requires a specific type. Only when you try to assign it to a typed variable would you get an error if it doesn't fit.

const bigNumber = 3e20 // OK - untyped constant

// var x int64 = bigNumber // ERROR - too big for int64

var y float64 = bigNumber // OK - fits in float64Input/Output Operations

Input (Scanning)

fmt.Scan

- Reads space-separated input from standard input

- Stops on first newline or whitespace

fmt.Scan(&a, &name)fmt.Scanln

- Reads input until newline (

\n) - Stops on newline instead of whitespace

fmt.Scanln(&a, &name)fmt.Scanf

- Reads formatted input using format specifiers (

%s,%d,%f) - Stops based on specified format

fmt.Scanf("%d %s", &a, &name)bufio.NewReader

- Advanced input reading capabilities

- Reads entire line including spaces

import "bufio"

reader := bufio.NewReader(os.Stdin)

reader.Scan()

input := reader.Text()

fmt.Println("You typed: %q",input)

reader := bufio.NewReader(os.Stdin)

input, _ := reader.ReadString('\n') // Reads entire line including spaces, stops on new lineOutput (Printing)

fmt.Print

- Prints values directly to console

- Concatenates values as strings

- No newline at end

fmt.Print("Hello", " ", "World!") // Output: Hello World!fmt.Println

- Prints values with newline at end

- Concatenates values with spaces between them

fmt.Println("Hello", "World!") // Output: Hello World!\nfmt.Printf

- Prints with formatting specifiers

- Uses

%s,%d,%v, etc. - No automatic newline (must specify

\n)

fmt.Printf("Name: %s, Age: %d\n", "Alice", 25)

fmt.Printf("%d %c\n", A[i], A[i]) // %d = ASCII value, %c = characterFormat verbs (common)

| Verb | Meaning | Example | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

%v | default format | fmt.Printf("%v\n", 123) | 123 |

%+v | include struct field names | fmt.Printf("%+v\n", struct{A int}{A:1}) | {A:1} |

%#v | Go-syntax representation | fmt.Printf("%#v\n", []int{1,2,3}) | []int{1, 2, 3} |

%T | type of the value | fmt.Printf("%T\n", 123) | int |

%t | boolean | fmt.Printf("%t\n", true) | true |

%b | base 2 | fmt.Printf("%b\n", 12) | 1100 |

%c | char (unicode) | fmt.Printf("%c\n", 65) | A |

%d | base 10 integer | fmt.Printf("%d\n", 123) | 123 |

%o | octal | fmt.Printf("%o\n", 8) | 10 |

%x, %X | hex (lower/upper) | fmt.Printf("%x\n", 255) | ff |

%f | decimal point for floats | fmt.Printf("%.2f\n", 3.14159) | 3.14 |

%e, %E | scientific notation | fmt.Printf("%e\n", 123400000.0) | 1.234000e+08 |

%g | compact floating format | fmt.Printf("%g\n", 1234.5) | 1234.5 |

%s | string | fmt.Printf("%s\n", "hello") | hello |

%q | quoted string | fmt.Printf("%q\n", "hello") | "hello" |

%p | pointer (address) | fmt.Printf("%p\n", &x) | 0xc000... |

%U | Unicode format (e.g. U+263A) | fmt.Printf("%U\n", '☺') | U+263A |

You can also use flags, width and precision with these verbs, for example: %5d, %-10s, %.2f, %05d.

fmt.Sprint

- Concatenates values into string without formatting

- Doesn't print to console, returns string

- No newline

message := fmt.Sprint("Hello", " ", "World!")

fmt.Println(message)fmt.Sprintln

- Concatenates values into string with newline

- Returns string with newline

message := fmt.Sprintln("Hello", "World!")

fmt.Print(message)fmt.Sprintf

- Formats values into string using format specifiers

- Returns formatted string

- No newline unless explicitly added

message := fmt.Sprintf("Name: %s, Age: %d", "Alice", 25)

fmt.Println(message)fmt.Fprint

- Writes formatted output to specified writer (files, buffers, etc.)

import (

"os"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

fmt.Fprint(os.Stdout, "Hello World!")

}Control Flow

Conditionals

If-Else

if a < b {

// code

} else if a > c {

// code

} else {

// code

}

// Statement can precede conditional

if num := 9; num < 0 {

// num is available here and in all subsequent branches

}Note: There is no ternary operator in Go. You'll need to use a full if statement even for basic conditions.

Statement-Statement Idiom:

You can declare and initialize variables within the if statement itself:

if z := a; z > n {

// z is available in this scope

fmt.Println(z)

}

// z is not available hereComma-Ok Idiom:

Used to check if a key exists in a map or if a channel receive was successful:

// With maps

if val, ok := m[key]; ok {

// Key exists, use val

fmt.Println(val)

} else {

// Key doesn't exist

fmt.Println("Key not found")

}

// Shorthand

val, ok := m[key]

if !ok {

fmt.Println("Key not found")

}Switch

You can use commas to separate multiple expressions in the same case statement.

switch i {

case 1:

// code

case 2, 3, 4: // Multiple values

// code

case i < 10: // Conditional expression

// code

case 'a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u':

// code

case "yes":

// code

default:

// code

}

// Switch without expression (alternate if-else)

switch {

case a < 12:

fmt.Println("It's before noon")

default:

fmt.Println("It's after noon")

}Features:

- Can use commas to separate multiple expressions

defaultis optionalbreakandfallthrough(executes just the next case as well) keywords available

Loops

For Loop

for i, j := 0, len(A)-1; i < j; i, j = i+1, j-1 {

// code

}Range Loop

Range loops provide a convenient way to iterate over elements in various data structures:

// Slice or Array

for i, v := range slice {

// i = index, v = value

fmt.Printf("Index: %d, Value: %d\n", i, v)

}

// Map

for k, v := range map {

// k = key, v = value

fmt.Printf("Key: %s, Value: %d\n", k, v)

}

// String (iterates over runes, not bytes)

for i, c := range "hello" {

// i = byte index (not rune index!), c = rune

fmt.Printf("Byte index: %d, Character: %c\n", i, c)

}

// Ignore index/key with _

for _, v := range slice {

fmt.Println(v)

}

// Just get index/key

for i := range slice {

fmt.Println(i)

}Functions

Basic Function

func addTwoNums(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

result := addTwoNums(1, 2)Function Signature

func (r receiver) identifier(p parameters) (r returns) { code }

Anonymous Functions

An anonymous function is a function literal defined without a name.

Two ways to use anonymous functions:

- Immediate Invocation - Call it right where you define it

- Assignment to a Variable - Store it for later use

// Function literal assigned to variable

hypot := func(x, y float64) float64 {

return math.Sqrt(x*x + y*y)

}

fmt.Println(hypot(5, 12))

// Immediate invocation (no parameters)

func() {

fmt.Println("Hi!")

}()

// Immediate invocation with parameters

func(name string) {

fmt.Println("Hello,", name)

}("Alice")Variadic Functions

- Can be called with any number of trailing arguments. For example, fmt.Println is a common variadic function.

func dum(num ...int) {

fmt.Print(num) // Equivalent to []int

}

func main() {

dum(2, 4)

dum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

}Named Return Values

A return statement without arguments returns the named return values. This is known as a "naked" return.

func split(sum int) (x, y int) {

x = sum * 4 / 9

y = sum - x

return // "naked" return

}Note: Naked returns should only be used in short functions for readability.

Closures

A closure is a function that remembers variables from its creation environment. Closures are particularly useful when working with goroutines and callbacks.

// i is used inside the func from outside func

func intSeq() func() int { // the Factory

i := 0 // Blueprint: "Every machine gets a private memory 'i' starting at 0."

// Blueprint: "The machine we build is a function that does this:"

return func() int {

i++ // Pressing the button adds 1 to its private 'i'.

return i // Then it returns the new value of 'i'.

}

}

f := intSeq()

fmt.Println(f()) // 1

fmt.Println(f()) // 2

fmt.Println(f()) // 3

g := intSeq()

fmt.Println(g()) // 1

fmt.Println(g()) // 2Understanding Closures: The Factory Analogy

Think of intSeq() as a factory that builds counter machines:

The Factory (intSeq function):

- Its only job is to build and return a new "counter" function.

The Private Memory (i variable):

- When the factory builds a counter, it gives it a private memory (

i) that starts at 0. - This memory is unique to each counter.

The Machine (the returned func()):

- This is the actual counter function. It has one job: add 1 to its private memory (

i) and return the new value. - It "closes over" or "remembers" its own

ibetween calls.

In Code:

f := intSeq()is ordering your first machine. It gets its own private memory.g := intSeq()is ordering a second, separate machine. It has its own memory and doesn't affect the first one.

Each time you call f(), it's like pressing a button on your first counter. Each time you call g(), it's like pressing a button on your second counter. They're independent!

Fibonacci Closure Example:

func fibonacci() func() int {

f1, f2 := 0, 1

return func() int {

f := f1

f1, f2 = f2, f+f2

return f

}

}

func main() {

f := fibonacci()

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

fmt.Println(f())

}

}Recursive Closures

Anonymous functions can also be recursive, but you need to declare the variable before defining the function.

var fib func(n int) int

// Must declare 'fib' variable first, then assign the function

// This is because the function body refers to 'fib' itself

fib = func(n int) int {

if n < 2 {

return n

}

return fib(n-1) + fib(n-2) // Calls itself

}

fib(10)Callback Functions

func doMath(a int, b int, f func(int, int) int) int {

return f(a, b)

}

func add(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

doMath(1, 2, add)Defer

A defer statement defers function execution until surrounding function returns.

func main() {

fmt.Println("counting")

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

defer fmt.Println(i)

}

fmt.Println("done")

}

// Output:

// counting

// done

// 2

// 1

// 0Key Points:

- Arguments evaluated immediately, but function call deferred

- Deferred calls pushed onto stack (LIFO execution)

- Useful for cleanup operations

func demonstrateArgumentEvaluation() {

i := 10

fmt.Printf("1. Declaring 'i' with value: %d\n", i)

defer fmt.Printf("3. Deferred print. Value of 'i' is: %d\n", i)

i = 20

fmt.Printf("2. After changing 'i', its value is now: %d\n", i)

}

// Output:

// 1. Declaring 'i' with value: 10

// 2. After changing 'i', its value is now: 20

// 3. Deferred print. Value of 'i' is: 10Data Structures

Arrays

Arrays do not change in size.

var a [5]int // Declaration

var a = [2]int{1, 2} // Initialize

var a = [...]int{1, 2} // Length inferred

a := [5]int{1: 2, 4: 3} // Initialize specific elements

a := [5]int{1, 2} // Partially initialized

fmt.Println(a[0]) // Access element

fmt.Println(a) // Print array

a[0] = 3 // Change element

len(a) // Length

// Multi-dimensional

twoD := [2][3]int{

{1, 2, 3},

{4, 5, 6},

}Slices

Slices are dynamic in size.

var a []int // nil slice

primes := []int{2, 3, 5} // Slice literal

numbers := make([]int, 5) // make(type, length)

data := make([]string, 0, 10) // make(type, length, capacity)

len(s) // Length

cap(s) // Capacity

s = append(s, "e", "f") // Append

copy(c, s) // Copy

l := s[2:5] // Slice s[2], s[3], s[4]

s[:5] // Exclude s[5]

s[2:] // Include s[2]

a = a[:n-1] // Resize length

slices.Equal(t, t2) // Compare slices

// Remove element

a = append(a[:2], a[3:]...) // Second arg must be unpacked with ...

// underlying array is copied, so that's why initializing the capacity while compile time is faster

s:=[]int{} // len:0 cap:0

s=append(s,1) // len:1 cap:1

s=append(s,2,3,4,5) // len:5 cap:6 <-1+5Important: Slices are Reference Types

a := []int{1, 2, 3}

b := a

a[0] = 4

// b[0] is now 4 - b references the same underlying array!

// To create independent copy:

b := make([]int, len(a))

copy(b, a)Capacity and Underlying Array

The capacity of a slice is the number of elements in the underlying array, counting from the first element in the slice.

s := []int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13} // len=6 cap=6

s = s[:4] // len=4 cap=6 (capacity unchanged)

s = s[2:] // len=2 cap=4 (capacity decreases!)Why capacity decreases: When you slice from index 2 onwards with s[2:], you're creating a new slice that starts at the 3rd element of the underlying array. The capacity is calculated from that starting point to the end of the underlying array. Since we're 2 elements from the start, capacity is reduced by 2 (from 6 to 4).

Important: Reslicing can extend a slice beyond its current length, up to its capacity:

s := []int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13}

s = s[:0] // len=0 cap=6

s = s[:4] // len=4 cap=6 - can reslice up to capacity!2D Slices

Go doesn't have true 2D arrays. 2D slices are slices of slices.

// Create 2D slice (n rows, m columns)

a := make([][]int, n)

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

a[i] = make([]int, m)

}

// Access elements

for i := 0; i < n; i++ {

for j := 0; j < m; j++ {

fmt.Scan(&a[i][j])

}

}

len(a) // Row length

len(a[0]) // Column lengthSorting Slices

sort.Ints(s) // Sort integers ascending

sort.Strings(s) // Sort strings ascendingMaps

Maps are unordered. Zero value is nil.

// Map literal

scores := map[string]int{

"Bob": 10,

"Alice": 9,

}

m := make(map[string]int) // Empty map

m := make(map[string]int, n) // With initial capacity

m["k1"] = 7 // Set value

len(m) // Length

delete(m, "k2") // Delete key/value

clear(m) // Remove all key/values

maps.Equal(n, n2) // Compare maps

// Comma-ok idiom

val, ok := m["k2"] // ok is true if key exists

if val, ok := m["k2"]; ok {

// key exists

}Omitting Type in Literals

If top-level type is just a type name, you can omit it from elements:

type Vertex struct {

Lat, Long float64

}

var m = map[string]Vertex{

"Bell Labs": {40.68433, -74.39967},

"Google": {37.42202, -122.08408},

}Strings

Strings are read-only slices of bytes encoded in UTF-8.

len(s) // Length

A[i] == 'a' // Check character

A[:len(A)-1] // Slice string

runes := []rune(A) // Convert to mutable rune slice (The standard Go idiom for building or modifying a string is to first convert it to a mutable slice of runes)

// String operations

s := "hey this is sk"

s1 := strings.Split(s, " ") // ["hey", "this", "is", "sk"] slice of strings [hey this is sk] but for A = " hello world " ["", "", "world", "", "", "hello", "", ""]

strings.Fields(A) // Handles multiple spaces - specifically designed to handle this. It treats one or more consecutive spaces as a single delimiter and automatically ignores any leading or trailing spaces.

strings.Join(A, " ") // Join with separator (hello world)

strings.Index(A, B) // Find substring index, gives index of b in a (aabaa, ba, 2)

// Range over strings

for i, c := range "go" {

// i is index, c is rune

}

// UTF-8 operations

import "unicode/utf8"

utf8.RuneCountInString(s) // Count runes, not bytesCharacter vs String

- Everything is binary. Characters use ASCII (e.g., 'a' = 97).

- In other languages, strings are made of “characters”. In Go, the concept of a character is called a rune - it’s an integer that represents a Unicode code point.

- strings are equivalent to []byte

var a rune // Rune declaration

A := "hello"

fmt.Printf("%d %c\n", A[i], A[i]) // %d = ASCII, %c = characterRune

A Go string is a read-only slice of bytes. The language and the standard library treat strings specially - as containers of text encoded in UTF-8. In other languages, strings are made of "characters". In Go, the concept of a character is called a rune - it's an integer that represents a Unicode code point.

Pointers

Go has no pointer arithmetic. Pointers are safer than in C/C++.

var p *int // Pointer to int

i := 10

p = &i // Address of i

fmt.Println(*p)// Read i through pointer (dereference)

*p = 21 // Set i through pointerPass by Value vs Reference

Everything in Go is passed by value unless it's a reference type:

- Pointers: A pointer holds the memory address of the value.

- Slices: A slice is a descriptor of an array segment. It includes a pointer to the array.

- Maps: A powerful data structure that associates values of one type with values of another type.

- Channels: Used for communication between goroutines.

- Functions and Interfaces.

func sliceChange(a []int) {

a[0] = 99

}

a := []int{1, 2, 3}

sliceChange(a)

fmt.Println(a[0]) // 99 - slice is reference type!Value vs Pointer Semantics

- When a function receives a value, it gets its own copy of that value. It will be typically placed in "THE STACK", which is fast and typically does not involve any form of garbage collection. Once the function returns, memory can be instantly reclaimed.

- When a function receives a pointer, it tells the compiler that this value could be shared across goroutine boundaries or it could be needed after the function call. So it will allocate it to "THE HEAP", which is more expensive and requires garbage collection.

- Try running go run -gcflags -m main.go (tells you if its moved to heap or not)

The Stack & The Heap

The Stack

- Stores local variables for functions/goroutines

- LIFO (Last-In-First-Out) structure

- Fast, automatic management

- Memory reclaimed when function returns

The Heap

- Stores variables with longer lifetime

- More flexible but slower

- Managed by garbage collector

- Used for shared or persistent data

Structs & Methods

Structs Basics

Structs are collections of fields. They are mutable.

package main

import "fmt"

type person struct {

name string

age int

}

type secretagent struct {

person // Nested struct (embedding)

ltk bool

}

func main() {

// Struct literal

p1 := person{

name: "Joe",

age: 28,

}

fmt.Println(p1)

fmt.Println(p1.name)

// Nested struct

sa1 := secretagent{

person: person{

name: "James B",

age: 35,

},

ltk: true,

}

fmt.Println(sa1)

fmt.Println(sa1.age) // Promoted field

// Anonymous struct

a := struct {

name string

}{

name: "SK",

}

fmt.Println(a)

}Struct Pointers

Pointers are automatically dereferenced. (*p).X notation is cumbersome.

p := &person{name: "Alice"}

fmt.Println(p.name) // Automatic dereferenceConstructors

- Constructors are special functions for reliably creating multiple instances of similar objects in a class-based OOP language.

- There is no specific definition for constructors in Go, but we can achieve the same functionality by writing a function (conventionally named

New...).

func newPerson(name string) *person {

p := person{name: name}

p.age = 42

return &p

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(newPerson("Jon")) // &{Jon 42}

}Abstraction

Defining behavior without implementation. This is the primary job of an interface. It defines a contract that other types can satisfy.

Constructor & Destructor

- Constructor: Go has no special constructor keyword. We use a factory function (by convention named

New...) to create and initialize our objects. - Destructor: Go is garbage-collected, so you don't manually destroy objects. For cleanup (like closing files), you use the

deferkeyword.

Methods

Go does not have classes. However, you can define methods on types.

type rect struct {

width, height int

}

// Pointer receiver (can modify)

func (r *rect) area() int {

return r.width * r.height

}

// Value receiver (read-only)

func (r rect) perim() int {

return 2*r.width + 2*r.height

}

func main() {

r := rect{width: 10, height: 5}

fmt.Println("area: ", r.area()) // (&r).area() behind scenes

fmt.Println("perim:", r.perim())

rp := &r

fmt.Println("area: ", rp.area())

fmt.Println("perim:", rp.perim()) // (*rp).perim() behind scenes

}Method Sets

The method set of a type determines which interfaces it implements:

| Receiver Type | Can be called on |

|---|---|

| (t T) | T and *T |

| (t *T) | *T |

type circle struct {

radius float64

}

func (c *circle) area() float64 {

return 3.14 * c.radius * c.radius

}

type shape interface {

area() float64

}

func info(s shape) {

fmt.Println("Area", s.area())

}

func main() {

c := circle{5}

fmt.Println(c.area()) // Works: compiler adds &

info(&c) // Must pass pointer

// info(c) // Won't work with interface!

}Struct Sorting

Implement sort.Interface methods: Len(), Swap(), Less()

type Person struct {

Name string

Age int

}

type ByAge []Person

func (a ByAge) Len() int { return len(a) }

func (a ByAge) Swap(i, j int) { a[i], a[j] = a[j], a[i] }

func (a ByAge) Less(i, j int) bool { return a[i].Age < a[j].Age }

func main() {

people := []Person{

{"Bob", 31},

{"John", 42},

{"Michael", 17},

{"Jenny", 26},

}

fmt.Println(people)

// One can define a set of methods for the slice type, as with ByAge, and call sort.Sort.

sort.Sort(ByAge(people))

fmt.Println(people)

}Composition

- Go uses composition over inheritance. Embed structs to reuse code.

- The fields and methods of the embedded "inner" struct become accessible to the outer struct.

- This concept is similar to inheritance in traditional object-oriented languages, but Go does not have a built-in inheritance mechanism.

In Go there are no classes, you create a type!

type Engine struct {

// Engine fields

}

func (e *Engine) Start() {

fmt.Println("Engine started")

}

type Car struct {

Engine // Embedding

// Car-specific fields

}

func main() {

car := Car{}

car.Start() // Promoted method

}Interfaces

Interface Basics & Implicit Implementation

Go uses duck typing: "If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it's a duck."

In the example below, we have a gasEngine and an electricEngine. They work differently internally, but they share a common behavior: calculating how many miles are left.

Because both structs have the milesLeft() method, they automatically implement the engine interface.

package main

import "fmt"

// 1. Define the Interface (The Contract)

type engine interface {

milesLeft() uint8

}

// 2. Define the Concrete Types

type gasEngine struct {

mpg uint8

gallons uint8

}

type electricEngine struct {

mpkwh uint8

kwh uint8

}

// 3. Implement the methods (implicitly satisfying the interface)

func (e gasEngine) milesLeft() uint8 {

return e.gallons * e.mpg

}

func (e electricEngine) milesLeft() uint8 {

return e.kwh * e.mpkwh

}

// 4. Use the Interface (Polymorphism)

// This function accepts ANY struct that satisfies the 'engine' interface

func canMakeIt(e engine, miles uint8) {

if miles <= e.milesLeft() {

fmt.Println("You can make it there!")

} else {

fmt.Println("Need to fuel up first!")

}

}

func main() {

// Create a specific type (electricEngine)

var myEngine electricEngine = electricEngine{25, 15}

// Pass it to a function expecting an 'engine' interface

canMakeIt(myEngine, 50)

// We could also pass a gasEngine here and it would work the same way!

}Composition Over Inheritance

- Go favors composition over inheritance.

- In traditional OOP, you have inheritance: Dog -> Animal, Manager -> Employee

- Instead, Go favors composition over inheritance. You achieve this through embedding. Instead of saying a Manager is an Employee, you say a Manager has an Employee record inside it.

Example: Manager/Employee

type Employee struct {

Name string

ID string

}

func (e Employee) Display() {

fmt.Printf("Name: %s, ID: %s\n", e.Name, e.ID)

}

type Manager struct {

Employee // Embedding (not inheritance!)

Reports []string

}

func main() {

m := Manager{

Employee: Employee{Name: "Alice", ID: "E123"},

Reports: []string{"Bob", "Charlie"},

}

// Because Employee is embedded, we can access its fields and methods directly

m.Display() // Prints: Name: Alice, ID: E123

// This LOOKS like inheritance, but it's composition

// Manager doesn't inherit from Employee; it contains an Employee

}Understanding Interfaces and Polymorphism

- Polymorphism is the ability to treat different objects in the same way. In Java, you might have a Shape class and different subclasses (Circle, Square) that you can put into a List. (Value can be any type)

- Go achieves this with interfaces, but it does so implicitly. You don't have to declare "my type implements this interface." You just implement the required methods. This is often called "duck typing."

- Polymorphism means a variable of one type (an interface) can hold a value of another type (a struct).

The USB-C Port Analogy:

Think of an interface like a USB-C port on your laptop. The port doesn't care if you're plugging in a phone, tablet, or headphones - as long as the device has a USB-C connector, it will work.

How Go's Compiler Checks Interfaces (Duck Typing):

When Go sees canMakeIt(myEngine):

- "The

canMakeItfunction needs anengine." - "The contract for

engineis a method calledmilesLeft() uint8." - "I'm being given a variable

myEngineof typeelectricEngine." - "Let me check the

electricEnginetype... Does it have a method calledmilesLeft() uint8? ...Yes, it does!" - "Great. That means

electricEngineimplicitly implementsengine. The code is valid."

Key Point: In Go, you don't declare that you are fulfilling a contract. You simply prove it by having the right methods. If you have the methods, you implement the interface automatically.

Go's OOP Approach

While Go isn't a traditional object-oriented language, it provides its own unique tools to achieve the same goals.

| Goal | Traditional OOP | Go Way |

|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation | class with fields/methods | struct with methods |

| Code Reuse | Inheritance (is-a) | Composition (has-a) |

| Polymorphism | Explicit interfaces | Implicit interfaces (duck typing) |

| Hierarchy | Central concept | No hierarchies |

| Objects | Complex with constructors | Simple structs |

Go is OOP? Yes and no

Go is OOP? Yes and no — it provides its own unique tools to achieve the same goals.

Why People Say "Yes, Go is OOP-like"

- Encapsulation — Go supports encapsulation, which is a core pillar of OOP. Encapsulation is bundling data and the methods that operate on that data together.

- In Go, you use structs and methods to group data and behavior.

- Access control is handled at the package level (capitalization determines export), rather than with per-field access modifiers found in some OOP languages.

Why People Say "No, Go is not OOP"

- Class vs type: Go has no

classkeyword or class-based inheritance; instead you definetype(usually structs) and attach methods to them. - Object vs instance: An object in class-based languages is an instance of a class that bundles data and methods together; in Go you build similar constructs from structs + methods.

- Inheritance: Traditional inheritance (subclassing) is not part of Go's design. Code reuse is achieved using composition (embedding), not

extends. - Polymorphism: Achieved via implicit interfaces (duck typing) rather than class hierarchies—types satisfy interfaces by implementing methods.

- Abstraction: Interfaces provide abstraction, but Go's approach differs from classical OOP abstractions (no abstract classes).

Key Differences:

- No classes (use structs)

- No inheritance (use composition)

- No explicit interface implementation

- No constructors/destructors (use factory functions and defer)

Summary: Go is OOP-like in spirit but different in implementation. It achieves encapsulation, code reuse, and polymorphism through structs, composition, and implicit interfaces rather than traditional OOP mechanisms.

Empty Interface (interface)

- An empty interface may hold values of any type. (Every type implements at least zero methods.)

- Empty interfaces are used by code that handles values of unknown type. For example,

fmt.Printtakes any number of arguments of typeinterface{}. - If the concrete value inside the interface itself is nil, the method will be called with a nil receiver.

In some languages this would trigger a null pointer exception, but in Go it is common to write methods that gracefully handle being called with a nil receiver.

func describe(i interface{}) {

fmt.Printf("(%v, %T)\n", i, i)

}

func main() {

var i interface{}

describe(i) // (<nil>, <nil>)

i = 42

describe(i) // (42, int)

i = "hello"

describe(i) // (hello, string)

}Type Assertions

A type assertion provides access to an interface value's underlying concrete value.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var i interface{} = "hello"

s := i.(string) // .(type) ...

fmt.Println(s)

s, ok := i.(string)

fmt.Println(s, ok)

f, ok := i.(float64)

fmt.Println(f, ok)

f = i.(float64) // panic

fmt.Println(f)

}Type Switches

A type switch is a construct that permits several type assertions in series.

import "fmt"

func do(i interface{}) {

switch v := i.(type) {

case int:

fmt.Printf("Twice %v is %v\n", v, v*2)

case string:

fmt.Printf("%q is %v bytes long\n", v, len(v))

default:

fmt.Printf("I don't know about type %T!\n", v)

}

}

func main() {

do(21)

do("hello")

do(true)

}Generics

Starting with version 1.18, Go has added support for generics, also known as type parameters.

Type Parameters

- Go functions can be written to work on multiple types using type parameters. The type parameters of a function appear between brackets, before the function's arguments.

- Comparable is a useful constraint that makes it possible to use the == and != operators on values of the type. func Index[T comparable](s []T, x T) int

func Index[T comparable](s []T, x T) int {

for i, v := range s {

if v == x {

return i

}

}

return -1

}

func main() {

si := []int{10, 20, 15, -10}

fmt.Println(Index(si, 15)) // 2

ss := []string{"foo", "bar", "baz"}

fmt.Println(Index(ss, "bar")) // 1

}Generic Types

Before generics, you had to use interface{} and lose type safety:

// OLD way (no type safety)

type OldList struct {

next *OldList

val any // Can be anything

}

// NEW way (type safe)

type List[T any] struct {

next *List[T]

val T

}Understanding Generic Type Syntax:

Let's break down what type List[T any] struct means step by step:

// 1. 2. 3.

type List[T any] struct {

next *List[T] // 4.

val T // 5.

}type List: We are declaring a new type namedList.[T]- The Type Parameter: This is the core of generics.Tis a placeholder for a real type that will be provided later. You can think of it as a variable, but for types. (You could call itValueType,Element, etc., butTis conventional.)any- The Constraint: This defines the "rules" for whatTis allowed to be. Theanyconstraint is the most permissive: it meansTcan be any type at all.next *List[T]: This means thenextfield must be a pointer to anotherListthat holds the exact same typeT. You can't link aListof integers to aListof strings. This enforces type safety throughout your data structure.val T: The value stored in this list node will have the typeT. If you create aListof ints,valwill be anint. If you create aListof strings,valwill be astring.

In simple terms:

type List[T any]means "I am defining a type calledListthat can work on any type, and we'll call that placeholder typeTfor now."

Why this matters:

Before generics, when you retrieved a value from OldList, Go only knew its type was any. You had to manually check its real type ("is this an int or a string?") and convert it. This is clumsy and can lead to errors at runtime if you guess wrong.

With generics, the type is known at compile time, giving you full type safety and better performance.

Type Constraints

// Basic constraint

func addT[T int|float64](a, b T) T {

return a + b

}

// Type set interface

type nums interface {

int | float64

}

func addT[T nums](a, b T) T {

return a + b

}Underlying Type Constraints

Use ~ to include all types with an underlying type:

type nums interface {

~int | ~float64 // Includes custom types with int/float64 as underlying type

}

func addT[T nums](a, b T) T {

return a + b

}

type blah int

func main() {

var a blah = 10

fmt.Println(addT(a, 2)) // Works with ~int

}Concurrency

"Concurrency is not parallelism." - Rob Pike

Concurrency vs Parallelism

Concurrency:

- Design pattern for code that can execute multiple tasks independently

- Potential for simultaneous execution

- Achieved with goroutines and channels

Parallelism:

- Actually executing multiple tasks at the same time

- Requires multiple CPUs/cores

- Runtime decides when to use parallelism

Sequential Execution:

- Opposite of parallel

- One task at a time in predefined order

Goroutines & WaitGroups

| Goroutine | Thread |

|---|---|

| Managed by Go runtime | Managed by OS Kernal |

| 2KB | 1MB |

| Abstraction of an actual thread | Hardware Dependent |

| cheap, lightweight and fast | Higher cost and start time |

Goroutines are lightweight threads managed by the Go runtime. A WaitGroup is used to wait for a collection of goroutines to finish executing.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

"runtime"

)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func foo() {

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

fmt.Println("foo:", i)

}

}

func bar() {

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

fmt.Println("bar:", i)

}

wg.Done()

}

func main() {

foo()

wg.Add(1)

fmt.Println("OS", runtime.GOOS)

fmt.Println("ARCH", runtime.GOARCH)

fmt.Println("CPU", runtime.NumCPU())

fmt.Println("Goroutines", runtime.NumGoroutine()) // 1

go bar() // Launch goroutine

fmt.Println("Goroutines", runtime.NumGoroutine()) // 2

wg.Wait() // Wait for goroutine to finish

}foo: 0

foo: 1

foo: 2

OS linux

ARCH amd64

CPU 1

Goroutines 1

Goroutines 2

bar: 0

bar: 1

bar: 2Race Conditions

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

"sync"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println("Goroutines:", runtime.NumGoroutine())

counter := 0 // shared memory for all goroutines

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(5)

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

go func() { // function literal/anonymous function

v := counter

runtime.Gosched() // pause the current goroutine and give another goroutine a chance to run.

v++

counter = v

wg.Done()

}()

fmt.Println("Goroutines:", runtime.NumGoroutine())

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Goroutines:", runtime.NumGoroutine())

fmt.Println("count:", counter)

}go run -race main.go # -race will tell you if there is any race condition (Found: 1 data race)

Goroutines: 1

Goroutines: 2

Goroutines: 3

Goroutines: 4

Goroutines: 5

Goroutines: 6

Goroutines: 1

count: 1Mutex (Preventing Race Conditions)

How to prevent race conditions? Answer: Use a Mutex.

- When a goroutine accesses shared memory, it should lock it so it cannot be accessed by other goroutines simultaneously.

func main() {

fmt.Println("Goroutines:", runtime.NumGoroutine())

counter := 0

var wg sync.WaitGroup

var mu sync.Mutex

wg.Add(5)

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

go func() {

mu.Lock() // Lock prevents other goroutines from accessing shared memory

v := counter

runtime.Gosched() // pause/yield the current goroutine and give another goroutine a chance to run.

v++

counter = v

mu.Unlock()

wg.Done()

}()

fmt.Println("Goroutines:", runtime.NumGoroutine())

}

wg.Wait()

fmt.Println("Goroutines:", runtime.NumGoroutine())

fmt.Println("count:", counter)

}Goroutines: 1

Goroutines: 2

Goroutines: 3

Goroutines: 4

Goroutines: 5

Goroutines: 6

Goroutines: 1

count: 5Channels

Channels are the pipes that connect concurrent goroutines. You can send values into channels from one goroutine and receive those values into another goroutine.

Channels are typed by the values they convey.

"Don't communicate by sharing memory; share memory by communicating."

Won't work

func main() {

c:=make(chan int) // unbuffered channel

c<- 42 // main goroutine blocks here because it's waiting for a receiver

fmt.Println(<-c)

}

// deadlock: all goroutines are asleepFix: Goroutine

Unbuffered Channels

func main() {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

c <- 42 // Send

}()

fmt.Println(<-c) // Receive

}Buffered Channels

func main() {

c := make(chan int, 1) // Buffer size 1

c <- 42 // Won't block

fmt.Println(<-c)

}Directional Channels

package main

import "fmt"

func ping(pings chan<- string, msg string) {

pings <- msg

}

func pong(pings <-chan string, pongs chan<- string) {

msg := <-pings

pongs <- msg

}

func main() {

pings := make(chan string, 1)

pongs := make(chan string, 1)

ping(pings, "passed message")

pong(pings, pongs)

fmt.Println(<-pongs)

}$ go run channel-directions.go

passed messageRange Over Channels

func foo(c chan<- int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

c <- i

}

close(c) // Must close or deadlock!

wg.Done()

}

func bar(c <-chan int, wg *sync.WaitGroup) {

for v := range c { // Reads until closed

fmt.Println(v)

}

wg.Done()

}Select

Go's select lets you wait on multiple channel operations. Combining goroutines and channels with select is a powerful feature of Go.

The select statement lets a goroutine wait on multiple communication operations. It blocks until one of its cases can proceed, then executes that case. If multiple cases are ready, it chooses one at random.

Select statement waits on multiple channel operations: "I am ready to receive from odd, even, OR quit. I will proceed with whichever one sends me a value first."

func send(odd, even, quit chan<- int) {

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

if i%2 == 0 {

even <- i

} else {

odd <- i

}

}

quit <- 0

}

func receive(odd, even, quit <-chan int) {

for {

select {

case v := <-odd:

fmt.Println("Odd:", v)

case v := <-even:

fmt.Println("Even:", v)

case v := <-quit:

fmt.Println("Quit:", v)

return

}

}

}

func main() {

odd := make(chan int)

even := make(chan int)

quit := make(chan int)

go send(odd, even, quit)

receive(odd, even, quit)

}Fan-In Pattern

Taking values from many channels and putting them onto one channel.

func send(odd, even chan<- int) {

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

if i%2 == 0 {

even <- i

} else {

odd <- i

}

}

close(even)

close(odd)

}

func receive(odd, even <-chan int, fanin chan<- int) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(2)

go func() {

for v := range odd {

fanin <- v

}

wg.Done()

}()

go func() {

for v := range even {

fanin <- v

}

wg.Done()

}()

wg.Wait()

close(fanin)

}

func main() {

odd := make(chan int)

even := make(chan int)

fanin := make(chan int)

go send(odd, even)

go receive(odd, even, fanin)

for v := range fanin {

fmt.Println(v)

}

}Rob pike - https://go.dev/talks/2012/concurrency.slide#28

Timeouts

Timeouts are important for programs that connect to external resources or that otherwise need to bound execution time. Implementing timeouts in Go is easy and elegant thanks to channels and select.

c1 := make(chan string, 1)

go func() {

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

c1 <- "result 1"

}()

select {

case res := <-c1:

fmt.Println(res)

case <-time.After(1 * time.Second):

fmt.Println("timeout 1")

}Non-Blocking Channel Operations

Basic sends and receives on channels are blocking. However, we can use select with a default clause to implement non-blocking sends, receives, and even non-blocking multi-way selects.

select {

case msg := <-messages:

fmt.Println("received message", msg)

default:

fmt.Println("no message received")

}WaitGroups Example

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

wg.Go(func() {

worker(i)

})

}Rate Limiting

Rate limiting is an important mechanism for controlling resource utilization and maintaining quality of service. Go elegantly supports rate limiting with goroutines, channels, and tickers.

requests := make(chan int, 5)

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

requests <- i

}

close(requests)

limiter := time.Tick(200 * time.Millisecond)

for req := range requests {

<-limiter

fmt.Println("request", req, time.Now())

}Fan-Out Pattern

The fan-out pattern distributes work across multiple goroutines to process tasks concurrently, then gathers (fans-in) the results. This pattern is useful for parallelizing CPU-intensive operations.

Distributing work across multiple goroutines and gathering results:

func populate(c1 chan<- int) {

for i := 1; i <= 5; i++ {

c1 <- i

}

close(c1)

}

func fanOutIn(c1, c2 chan int) {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

for v := range c1 {

wg.Add(1)

go func(value int) {

c2 <- doSomething(value)

wg.Done()

}(v)

}

wg.Wait()

close(c2)

}

func doSomething(v int) int {

return v + 10

}

func main() {

c1 := make(chan int)

c2 := make(chan int)

go populate(c1)

go fanOutIn(c1, c2)

for v := range c2 {

fmt.Println(v)

}

}In short: You Fan-Out to do work faster, and then Fan-In to gather all the results.

Context

- Context is tool that you can use with concurrent design patterns.

- In Go servers, each incoming request is handled in its own goroutine. Request handlers often start additional goroutines to access backends such as databases and RPC services. The set of goroutines working on a request typically needs access to request-specific values such as the identity of the end user, authorization tokens, and the request’s deadline. When a request is canceled or times out, all the goroutines working on that request should exit quickly so the system can reclaim any resources they are using. https://go.dev/blog/context

Error Handling

Go's Error Philosophy

- Go avoids exceptions for more readable and predictable code.

- In many languages, exceptions are like hidden "gotos." A function can suddenly stop and jump to a catch block far away, making the code's flow difficult to follow.

- Instead, Go treats errors as regular values. A function that might fail simply returns the error alongside its normal result.

- This explicit error handling makes code more verbose but also more transparent and easier to reason about.

Error Interface

type error interface {

Error() string

}errors.As - It checks that a given error (or any error in its chain) matches a specific error type and converts to a value of that type, returning true. If there's no match, it returns false.

Error Handling Options

// fmt.Println - simple print

fmt.Println(err)

// log.Println - prints with date/time

log.Println(err)

// log.Fatalln - exits program

log.Fatalln(err) // Deferred functions do NOT run

// log.Panicln - stops current goroutine

log.Panicln(err) // Deferred functions run

// panic - stops normal execution

panic(err) // Deferred functions runCreating Errors

import (

"errors"

"fmt"

)

// errors.New

func isTrue(b bool) (bool, error) {

if !b {

return false, errors.New("It was False")

}

return true, nil

}

// fmt.Errorf

func isTrue(b bool) (bool, error) {

if !b {

return false, fmt.Errorf("It was False")

}

return true, nil

}Custom Error Types

type MyError struct {

When time.Time

What string

}

func (e *MyError) Error() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("at %v, %s",

e.When, e.What)

}

func run() error {

return &MyError{

time.Now(),

"it didn't work",

}

}

func main() {

if err := run(); err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

}Error Handling Idiom

_, err := fmt.Println("hello")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}Logging to File

func main() {

f, err := os.Create("log.txt")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer f.Close()

log.SetOutput(f)

f2, err := os.Open("no-file.txt")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln(err) // Writes to log.txt and exits

}

defer f2.Close()

}Recover

Built-in function to regain control of panicking goroutine. Only useful in deferred functions.

package main

import "fmt"

func mayPanic() {

panic("a problem")

}

func main() {

defer func() {

if r := recover(); r != nil {

fmt.Println("Recovered. Error:\n", r)

}

}()

mayPanic()

fmt.Println("After mayPanic()")

}$ go run recover.go

Recovered. Error:

a problemTesting

Test File Structure

- Tests must be in files ending with

_test.go - Must be in same package

- Function signature:

func TestXxx(t *testing.T)

// main.go

func sum(a, b int) int {

return a + b

}

// main_test.go

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

if sum(2, 3) != 5 {

t.Error("Expected", 5, "Got", sum(2, 3))

}

}go test

PASS

ok test 3.459s

--- FAIL: TestSum (0.00s)

main_test.go:7: Expected 5 Got 6

FAIL

exit status 1

FAIL test 4.616sSubtests

- Use t.Run to create hierarchical tests.

- Allows you to group related tests and share setup code.

- Enables running specific subtests via command line flags (e.g., go test -run TestSum/Negative).

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

// Subtest 1: +ve numbers

t.Run("Positive", func(t *testing.T) {

if sum(2, 3) != 5 {

t.Error("Expected 5")

}

})

// Subtest 2: -ve numbers

t.Run("Negative", func(t *testing.T) {

if sum(-1, -2) != -3 {

t.Error("Expected -3")

}

})

}Table-Driven Tests

- The idiomatic way to test multiple cases.

- low overhead to add more test cases.

- Do this pattern a lot. Follow pattern even for single cases, if its possible to grow.

type testcase struct {

data []int

answer int

}

func TestSum(t *testing.T) {

tests := []testcase{

{

data: []int{2, 3},

answer: 5,

},

{

data: []int{7, 3},

answer: 10,

},

}

for _, tc := range tests {

result := sum(tc.data[0], tc.data[1])

if result != tc.answer {

t.Errorf("Expected %d, got %d", tc.answer, result)

}

}

}Benchmarking

Benchmarks run code repeatedly to get stable average execution time.

var result int

func BenchmarkSum(b *testing.B) {

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

result = sum(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

}

}Run benchmarks: go test -bench .

Output explanation:

go test -bench .

goos: windows

goarch: amd64

pkg: test

cpu: 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1245U

BenchmarkSum-12 305967357 4.197 ns/op 0 B/op 0 allocs/op

PASS

ok test 3.106sBenchmarkSum-12: Test name and number of CPUs305967357: Number of iterations run4.197 ns/op: Average time per operation0 B/op: Bytes allocated per operation0 allocs/op: Number of allocations per operation

Test Coverage

Check what percentage of your code is tested:

go test -cover

PASS

coverage: 80.0% of statements

ok test 9.639sGenerate detailed coverage report:

go test -coverprofile=coverage.out

go tool cover -html=coverage.outLinting and Code Quality

Tools to improve code quality:

go fmt ./... # Format code automatically

go vet ./... # Report suspicious constructs

golint ./... # Report poor coding style (install separately)go fmt: Automatically formats your code according to Go standards.

go vet: Examines Go source code and reports suspicious constructs (unreachable code, improper use of range, etc.).

golint: Reports style mistakes (exported functions without comments, naming conventions, etc.).

Standard Library & Packages

Common Packages

fmt // Formatting I/O

math // Mathematical functions

strings // String manipulation

sort // Sorting

time // Time/date operations

os // OS interface

io // I/O primitives

bufio // Buffered I/O

errors // Error creation

log // Logging

sync // Synchronization primitivesMath Package

math.Floor(x) // Greatest integer ≤ x

math.Ceil(x) // Least integer ≥ x

math.Round(x) // Nearest integer

math.Pow(x, y) // x^y

math.Pi // 3.14159265...

math.MinInt64 // -9,223,372,036,854,775,808Strings Package

strings.Split(s, " ") // Split string

strings.Fields(s) // Split on whitespace (handles multiple spaces)

strings.Join(slice, " ") // Join with separator

strings.Index(s, substr) // Find substringPrintf vs Sprintf: Printf prints the formatted string to os.Stdout. Sprintf formats and returns a string without printing it anywhere.

Init Function

Called after variable declarations, after all imported packages initialized:

func init() {

if user == "" {

log.Fatal("$USER not set")

}

}Note: init is a niladic function (Function does not have an argument).

Advanced Concepts

UTF-8 Encoding

- UTF-8 is an encoding system for Unicode

- Variable length: 1-4 bytes per character

- ASCII characters: 1 byte

- Most common approach: efficient memory use

| Concept | What it is | How it works |

|---|---|---|

| ASCII | Basic keyboard for English | 128 characters (7 bits) |

| Unicode | Universal character catalog | Unique number for every character/emoji/symbol |

| UTF-8 | Smart storage method | Variable 1-4 bytes per character |

Character Increment

var c rune = 'A'

c++ // 'B'

// Example pattern

// n=4

// A

// B B

// C C C

// D D D DDocumentation (godoc)

godoc -http :8080 # Run local doc serverComments above functions generate documentation. Also use doc.go files.

Sorting

strs := []string{"c", "a", "b"}

slices.Sort(strs) // Strings: [a b c]Sorting by Functions

Sometimes we'll want to sort a collection by something other than its natural order. For example, suppose we wanted to sort strings by their length instead of alphabetically. Here's an example of custom sorts in Go.

fruits := []string{"peach", "banana", "kiwi"}

lenCmp := func(a, b string) int {

return cmp.Compare(len(a), len(b))

}

slices.SortFunc(fruits, lenCmp)

fmt.Println(fruits) // [kiwi peach banana]Stringer Interface

The Stringer interface allows types to describe themselves as strings. fmt.Println looks for any type that implements the Stringer interface (i.e., has a String() method) and uses it to get a string representation.

If a type (like Person) didn't have a String() method, Println would print something like {Arthur Dent 42} instead.

This is one of Go's most powerful patterns—interface-based polymorphism.

// Defined in fmt package

type Stringer interface {

String() string

}Example implementation:

package main

import "fmt"

type Person struct {

Name string

Age int

}

func (p Person) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("%s (%d years old)", p.Name, p.Age)

}

func main() {

p := Person{Name: "Arthur Dent", Age: 42}

fmt.Println(p) // Arthur Dent (42 years old)

}Writer Interface

The io.Writer interface is one of the most important interfaces in Go's standard library. It represents any type that can write bytes.

// Defined in io package

type Writer interface {

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

}Example usage:

package main

import (

"bytes"

"fmt"

"io"

"log"

"os"

)

type person struct {

first string

}

// writeOut accepts any type that implements io.Writer

func (p person) writeOut(w io.Writer) {

w.Write([]byte(p.first))

}

func main() {

p := person{

first: "Jenny",

}

// Write to a file

f, err := os.Create("output.txt")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("error %s", err)

}

defer f.Close()

// Write to a buffer

var b bytes.Buffer

// Same method works with both file and buffer!

p.writeOut(f) // Writes to file

p.writeOut(&b) // Writes to buffer

fmt.Println(b.String()) // Prints: Jenny

}Why this is powerful:

- Your code doesn't care if it's writing to a file, network connection, or in-memory buffer

- Any type that implements

Write([]byte) (int, error)can be used - This is polymorphism in action

Summary

Go is a modern, statically-typed language designed for:

- Simplicity: Clean syntax, easy to learn

- Concurrency: Built-in goroutines and channels

- Performance: Compiled, efficient execution

- Reliability: Strong typing, garbage collection

- Practicality: Great standard library, fast compilation

Core Philosophy:

- Less is more (minimalist design)

- Composition over inheritance

- Explicit over implicit

- Concurrency is not parallelism

- Don't communicate by sharing memory; share memory by communicating

Command-Line Arguments

Command-line arguments are a common way to parameterize execution of programs. For example, go run hello.go uses run and hello.go arguments to the go program.

argsWithProg := os.Args // os.Args provides access to raw command-line arguments. Note that the first value in this slice is the path to the program.

argsWithoutProg := os.Args[1:] // holds the arguments to the program$ go build command-line-arguments.go

$ ./command-line-arguments a b c d

[./command-line-arguments a b c d]

[a b c d]Command-Line Flags

Command-line flags are a common way to specify options for command-line programs. For example, in wc -l the -l is a command-line flag.

wordPtr := flag.String("word", "foo", "a string") // string flag word with a default value "foo" and a short description.

numbPtr := flag.Int("numb", 42, "an int")

forkPtr := flag.Bool("fork", false, "a bool")

var svar string

flag.StringVar(&svar, "svar", "bar", "a string var")

flag.Parse() // to execute the command-line parsing.

fmt.Println("word:", *wordPtr)

fmt.Println("numb:", *numbPtr)

fmt.Println("fork:", *forkPtr)

fmt.Println("svar:", svar)

fmt.Println("tail:", flag.Args())

// Command-Line Subcommands

fooCmd := flag.NewFlagSet("foo", flag.ExitOnError)

fooEnable := fooCmd.Bool("enable", false, "enable")$ ./command-line-flags -word=opt -numb=7 -fork -svar=flag a1 a2 # Trailing positional arguments can be provided after any flags.

word: opt

numb: 7

fork: true

svar: flag

tail: [a1, a2]

$ ./command-line-subcommands foo -enable a1 a2 -name=joe # flag package requires all flags to appear before positional arguments (otherwise the flags will be interpreted as positional arguments).

subcommand 'foo'

enable: true

tail: [a1 a2 -name=joe]Environment Variables

Environment variables are a universal mechanism for conveying configuration information to Unix programs. Let's look at how to set, get, and list environment variables.

os.Setenv("FOO", "1")

fmt.Println("FOO:", os.Getenv("FOO"))

fmt.Println("BAR:", os.Getenv("BAR")) // This will return an empty string if the key isn't present in the environment.

fmt.Println()

for _, e := range os.Environ() { // list all key/value pairs in the environment. This returns a slice of strings in the form KEY=value.

pair := strings.SplitN(e, "=", 2)

fmt.Println(pair[0])

}URL Parsing

s := "http://admin:secret@example.com:8080/x/?abc=xyz#top"

u, err := url.Parse(s)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Println("Scheme:", u.Scheme)

fmt.Println("User:", u.User)

fmt.Println("Username:", u.User.Username())

p, _ := u.User.Password()

fmt.Println("Password:", p)

fmt.Println("Host (Full):", u.Host)

host, port, _ := net.SplitHostPort(u.Host)

fmt.Println("Split Host:", host)

fmt.Println("Split Port:", port)

fmt.Println("Path:", u.Path)

fmt.Println("Fragment:", u.Fragment) // The part after '#'

fmt.Println("RawQuery:", u.RawQuery)

m, _ := url.ParseQuery(u.RawQuery)

fmt.Println("Query Map:", m)

fmt.Println("Value of abc:", m["abc"][0])Base64 Encoding

Go provides built-in support for base64 encoding/decoding.

data := "abc123!?$*&()'-=@~"

sEnc := base64.StdEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(data)) // YWJjMTIzIT8kKiYoKSctPUB+

sDec, _ := base64.StdEncoding.DecodeString(sEnc) // abc123!?$*&()'-=@~

uEnc := base64.URLEncoding.EncodeToString([]byte(data)) // YWJjMTIzIT8kKiYoKSctPUB-

uDec, _ := base64.URLEncoding.DecodeString(uEnc) // abc123!?$*&()'-=@~SHA256 Hashes

SHA256 hashes are frequently used to compute short identities for binary or text blobs. For example, TLS/SSL certificates use SHA256 to compute a certificate's signature. Here's how to compute SHA256 hashes in Go.

s := "sha256 this string"

h := sha256.New() // Think of h as a "digest machine" that is waiting to be fed data.

h.Write([]byte(s)) // This feeds your data into the machine.

bs := h.Sum(nil) // calculates the final checksum. // 1af1dfa857bf1d8814fe1af8983c18080019922e557f15a8a...Time

now := time.Now() // prints the current time

then := time.Date(2009, 11, 17, 20, 34, 58, 651387237, time.UTC) // building the time

p(then.Year())

p(then.Month())

p(then.Day())

p(then.Hour())

p(then.Minute())

p(then.Second())

p(then.Nanosecond())

p(then.Location())

p(then.Weekday())

p(then.Before(now)) // These methods compare two times, testing if the first occurs before, after, or at the same time as the second, respectively.

p(then.After(now))

p(then.Equal(now))

now.Sub(then)Signals

Sometimes we'd like our Go programs to intelligently handle Unix signals. For example, we might want a server to gracefully shutdown when it receives a SIGTERM, or a command-line tool to stop processing input if it receives a SIGINT. Here's how to handle signals in Go with channels.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

"os/signal"

"syscall"

)

func main() {

sigs := make(chan os.Signal, 1) // Go signal notification works by sending os.Signal values on a channel. We'll create a channel to receive these notifications. Note that this channel should be buffered.

signal.Notify(sigs, syscall.SIGINT, syscall.SIGTERM)

done := make(chan bool, 1) // signal.Notify registers the given channel to receive notifications of the specified signals.

go func() {

sig := <-sigs

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println(sig)

done <- true

}()

fmt.Println("awaiting signal")

<-done

fmt.Println("exiting")

}

/*

$ go run signals.go

awaiting signal

^C

interrupt

exiting

*/JSON

Only exported fields will be encoded/decoded in JSON. Fields must start with capital letters to be exported.

strB, _ := json.Marshal("gopher")

fmt.Println(string(strB)) // "gopher"

str := `{"page": 1, "fruits": ["apple", "peach"]}`

res := response2{}

type response2 struct {

Page int `json:"page"`

Fruits []string `json:"fruits"`

}

res := response2{}

str := `{"page": 1, "fruits": ["apple", "peach"]}`

json.Unmarshal([]byte(str), &res) // parsing to a predefined struct

// Encode directly to Standard Output

enc := json.NewEncoder(os.Stdout)

d := map[string]int{"apple": 5, "lettuce": 7}

enc.Encode(d)

// Decode directly from a Reader

dec := json.NewDecoder(strings.NewReader(str))

res1 := response2{}

dec.Decode(&res1) // {1 [apple peach]}Templates

Go offers built-in support for creating dynamic content or showing customized output to the user with the text/template package.

Templates are a mix of static text and "actions" enclosed in {{...}} that are used to dynamically insert content.

Think of a Template as a letter with "blanks" to fill in. You write the text once, and then you "execute" it with different data to fill in the blanks.

t1 := template.New("t1")

t1, err := t1.Parse("Value: {{.}}\n")

t1 = template.Must(t1.Parse("Value: {{.}}\n"))

t1.Execute(os.Stdout, "some text") // Value: some text

t1.Execute(os.Stdout, 5) // Value: 5

Create := func(name, t string) *template.Template {

return template.Must(template.New(name).Parse(t))

}

// If the data is a struct we can use the {{.FieldName}} action to access its fields. The fields should be exported to be accessible when a template is executing.

t2 := Create("t2", "Name: {{.Name}}\n")

t2.Execute(os.Stdout, struct {

Name string

}{"Jane Doe"})

t2.Execute(os.Stdout, map[string]string{

"Name": "Mickey Mouse",

})

t3 := Create("t3", "{{if . -}} yes {{else -}} no {{end}}\n") // Ends the code and deletes the whitespace/newline immediately following it.

t3.Execute(os.Stdout, "not empty")

t3.Execute(os.Stdout, "")

t4 := Create("t4", "Range: {{range .}}{{.}} {{end}}\n")

t4.Execute(os.Stdout,

[]string{

"Go",

"Rust",

"C++",

"C#",

})File I/O

Reading Files

path := filepath.Join(os.TempDir(), "dat")

dat, err := os.ReadFile(path) // read entire file

fmt.Print(string(dat)) // hello\n go\n

f, err := os.Open(path)

b1 := make([]byte, 5) // set 5 byte

n1, err := f.Read(b1)

fmt.Printf("%d bytes: %s\n", n1, string(b1[:n1])) // 5 bytes: hello

o2, err := f.Seek(6, io.SeekStart) // You can also Seek to a known location in the file and Read from there.

b2 := make([]byte, 2)

n2, err := f.Read(b2)

fmt.Printf("%d bytes @ %d: %v\n", n2, o2, string(b2[:n2])) // 2 bytes @ 6: go

o3, err := f.Seek(6, io.SeekStart)

b3 := make([]byte, 2)

n3, err := io.ReadAtLeast(f, b3, 2)

fmt.Printf("%d bytes @ %d: %s\n", n3, o3, string(b3)) // 2 bytes @ 6: go

_, err = f.Seek(0, io.SeekStart) // There is no built-in rewind, but Seek(0, 0) accomplishes this.

r4 := bufio.NewReader(f)

b4, err := r4.Peek(5) // Peek returns the next n bytes without advancing the reader.

fmt.Printf("5 bytes: %s\n", string(b4)) // 5 bytes: hello

f.Close()Writing Files

d1 := []byte("hello\ngo\n")

path1 := filepath.Join(os.TempDir(), "dat1")

err := os.WriteFile(path1, d1, 0644) // 0644 represents the permission bits

path2 := filepath.Join(os.TempDir(), "dat2")

f, err := os.Create(path2)

defer f.Close()

d2 := []byte{115, 111, 109, 101, 10}

n2, err := f.Write(d2)

fmt.Printf("wrote %d bytes\n", n2) // wrote 5 bytes

n3, err := f.WriteString("writes\n") // writes a string.

fmt.Printf("wrote %d bytes\n", n3) // wrote 7 bytes

// Issue a Sync to flush writes to stable storage.

f.Sync()

w := bufio.NewWriter(f)

n4, err := w.WriteString("buffered\n")

fmt.Printf("wrote %d bytes\n", n4) // wrote 9 bytes

// Use Flush to ensure all buffered operations have been applied to the underlying writer.

w.Flush()Directories

err := os.Mkdir("subdir", 0755) // Create a new sub-directory.

defer os.RemoveAll("subdir") // Defer removal of the directory tree (like `rm -rf`).

err = os.MkdirAll("subdir/parent/child", 0755) // Create a hierarchy of directories (like `mkdir -p`).

c, err := os.ReadDir("subdir/parent") // List directory contents.

// Iterate over entries to print name and type.

for _, entry := range c {

fmt.Println(" ", entry.Name(), entry.IsDir())

}

// Temp Directory

f, err := os.CreateTemp("", "sample") // Create a temporary file.

fmt.Println("Temp file name:", f.Name()) // Temp file name: /tmp/sample610887201

defer os.Remove(f.Name()) // Clean up the file after we're done.

dname, err := os.MkdirTemp("", "sampledir") // Temp Directory (Temp dir name: /tmp/sampledir898854668)

defer os.RemoveAll(dname)

// embed

//go:embed is a compiler directive that allows programs to include arbitrary files and folders in the Go binary at build time.

// embed directives accept paths relative to the directory containing the Go source file. This directive embeds the contents of the file into the string variable immediately following it.

//go:embed folder/single_file.txt

var fileString string // hello go

//go:embed folder/single_file.txt

var fileByte []byte // hello go

//go:embed folder/single_file.txt

//go:embed folder/*.hash

var folder embed.FS

content1, _ := folder.ReadFile("folder/file1.hash")

print(string(content1)) // hello goTCP Server

package main

import (

"bufio"

"fmt"

"log"

"net"

"strings"

)

func main() {

listener, err := net.Listen("tcp", ":8090")

if err != nil {

log.Fatal("Error listening:", err)

}

defer listener.Close()

for {

conn, err := listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

log.Println("Error accepting conn:", err)

continue

}

go handleConnection(conn)

}

}

func handleConnection(conn net.Conn) {

defer conn.Close()

reader := bufio.NewReader(conn)

message, err := reader.ReadString('\n')

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Read error: %v", err)

return

}

ackMsg := strings.ToUpper(strings.TrimSpace(message))

response := fmt.Sprintf("ACK: %s\n", ackMsg)

_, err = conn.Write([]byte(response))

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Server write error: %v", err)

}

}

/*

$ go run tcp-server.go &

$ echo "Hello from netcat" | nc localhost 8090

ACK: HELLO FROM NETCAT

*/Learn More: